Beer Anatomy – India Pale Ale (IPA)

The Traveling Beer

Words: Mike Velez

From issue #2 of Beer Magazine

When you hear the word “bitter,” positive thoughts usually don’t come to mind. Of the five basic tastes, it’s probably the least pleasant. In fact, some biologists have theorized that our distaste for bitter substances evolved as a defense mechanism against accidental poisoning. However, it seems that many of us have taken a particular liking to foods and beverages that are bitter, such as unsweetened chocolate, coffee, mineral water, and most importantly, IPAs. Yup, the king of bitter beer is the IPA. Thanks to an abundance of hops, IPAs have a “great” bitter flavor that some beer connoisseurs have grown to love. This Beer Anatomy features everything you need to know about IPAs. Use this newfound knowledge wisely the next time you’re looking to pucker up or impress your friends with some British colonial trivia.

History

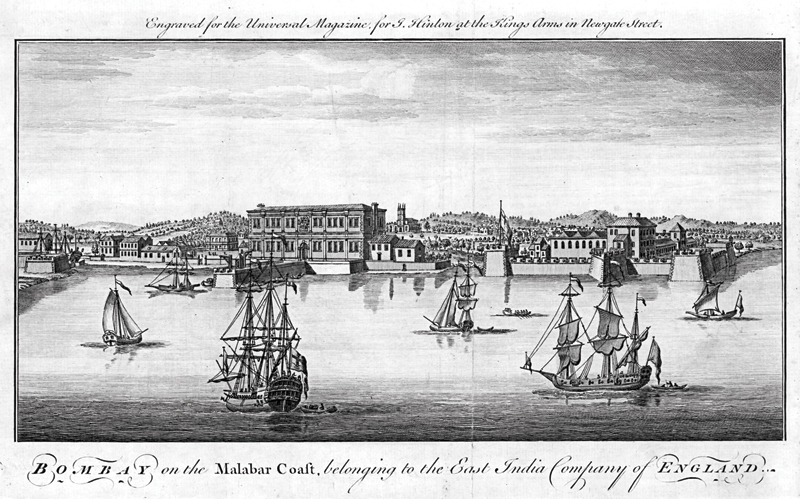

The first IPA was brewed in the 1790s by George Hodgson, a brewer at the Bow Brewery in East London, England. Back then, the British were pretty busy running their empire, and nothing fed a thirsty imperial army like beer. The long 3 to 5-month trip from London to India was taking its toll on the beers brewed at the time (porters and ales) while they were being shipped. The tropical climate surrounding the ports in India prevented successful brewing, so a solution had to be found. Brewers back home in England tried different packaging methods, keeping the ales on the coolest, lowest levels of the ships’ hulls. But even then the beer arrived musty, flat, and sour.

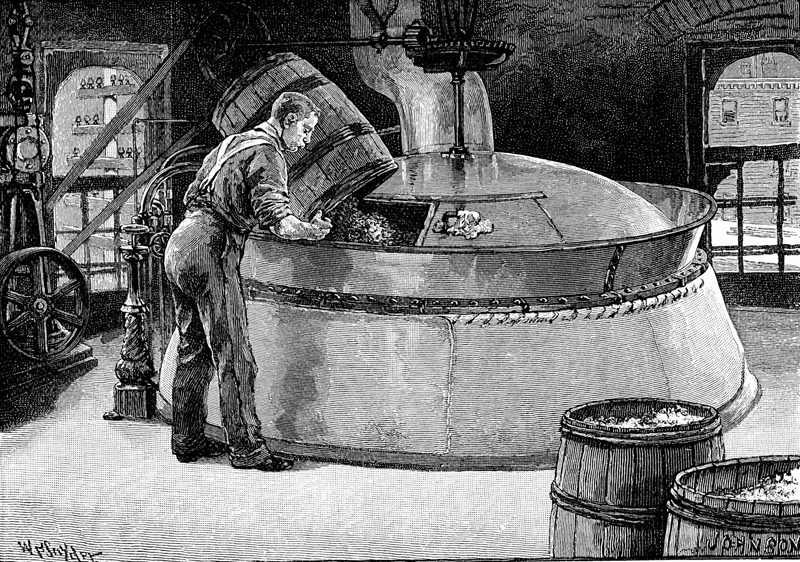

Before refrigeration, there were two tricks a creative brewer could use to fight spoilage: the use of hops, and alcohol content. Hops contain isohumulone, which is the substance that gives hops their bitterness. Isohumulone is also a natural enemy of lactobacillus, one of the bacteria that spoils beer. Alcohol is an enemy of bacteria as well. Mr. Hodgson recognized this and modified his pale ale recipe. He increased the hop content considerably, and also raised the alcohol content by adding extra grain and sugar before fermenting. The result was a very bitter, sparkling ale that could withstand long trips and unfavorable conditions. Both the recipe and the process have evolved, resulting in the modern IPA we’ve grown to love.

The Ingredients:

Water: When Mr. Hodgson first brewed his original IPA, he used what was available in London—water that was high in carbonate and low in sulfates. Over time, brewers found that higher sulfates and less carbonate resulted in a more pleasant hop bitterness. Today, American brewers use soft to moderate water to buffer the sulfate levels.

Hops: The magic ingredient that helps make an IPA an IPA is hops. The first IPA started as a pale ale that was heavily hopped, and this step in production still holds true today. In American IPAs, no particular strain of hops is routinely used to make this beer. However, one of the first American IPAs, Ballantine IPA, was brewed using Bullion hops. These hops are grown in England, and can also be found in Washington and Oregon. They are very bitter and perfect for an IPA. Cascade hops, grown in the Pacific Northwest, are used by many brewers for their bitterness. They’re not as bitter as Bullion hops, but they get the job done.

Malt: The malt used in the IPA brewing process is typically standard pale ale malt. This is usually two-row pale barley, the most common malt used in beers today.

Yeast: Like the malt used in pale ales, IPAs are made with the same type of yeast used to produce pale ales. This means top-fermenting brewers yeast that ferments quickly. It’s called top-fermenting because of the foam that forms at the top of the wort during fermentation. Top-fermenting yeast can produce the higher alcohol needed for the IPA, and is fermented at a higher temperature than a lager.

The Process

Remember, there are two distinct elements that separate an IPA from just any pale ale: a greater quantity of hops and a higher alcohol content. In the brewing process, more hops are added when the wort (what you get after the malt’s been mashed) is boiling. When boiled, the natural acids in the hops are converted into more soluble iso-alpha acids that help flavor the beer. Since boiling removes a significant amount of the flavor and aroma characteristics of the hops, more hops are added at different points during the boiling process. The first addition of hops gives the beer its bitterness. Later in the process, the hops that are added contribute to the hop flavor and aroma. The higher alcohol content comes from the fermenting process. IPAs are typically fermented at a higher temperature than most pale ales, and this higher temperature produces the higher alcohol content found in IPAs.

Common IPAs

English: Burton Bridge Empire IPA, Goose Island IPA, Samuel Smith’s India Pale Ale, Three Floyds ThulzaDoom English IPA

American: Stone IPA, Harpoon IPA, Avery IPA, Victory Hop Devil, BridgePort IPA, Great Divide Titan IPA, Dogfish Head 60 Minute IPA, Brooklyn East India Pale Ale, MacTarnahans IPA, Sierra Nevada IPA, Flying Dog Snake Dog IPA

Imperial/Double: Dogfish Head 120 minute IPA, Stone Ruination IPA, Southern Tier Un*Earthly Imperial IPA, Midnight Sun Gluttony, Bristol Edge City 1.5 IPA, Green Flash Imperial IPA, Smuttynose Big A IPA, Hair of the Dog Blue Dot Imperial IPA, Rogue Imperial India Pale Ale, Founders Imperial IPA, Full Sail Slipknot Imperial IPA

Variations

There are three basic variations of IPAs: English, American, and Imperial.

< ENGLISH

The English IPA has assertive hop bitterness, a moderate earthy and floral aroma, and a British flair of bread-like or biscuit flavor. It tends to go well with those crumpets. The beer typically has a medium finish with a hoppy aftertaste, but there’s nothing too harsh on the palate for those new to hoppy beers. This variation most closely resembles what George Hodgson brewed a few hundred years ago. The hop characteristic is not quite as intense as American IPAs, as English IPAs have a somewhat fruity taste.

< American

The American IPA is the most common of the IPAs and tends to have characteristics that make it a bit more intense than the English version, but less than the Imperial. It has a medium to high hoppy taste coupled with a low malty flavor that provides good balance. It’s typically reddish copper in color and has a high carbonation level. Thanks to the American hops used, this beer gives off an intense citrusy, piney, or floral aroma. For those looking to sample something hoppier than a pale ale, and with a bit more potency, the American IPA is a good place to start.

The Imperial IPA is the granddaddy of hoppiness. While its color may resemble that of the American or English IPAs, its absurdly high hop bitterness is impossible to mistake. The smell of the hops in this beer is very robust and pleasing to the senses, and it should be served in a brandy snifter glass to fully enjoy the aroma. The flavor explosion of an IPA can be attributed to an increase in the quantity and variety of hops, and the process of dry hopping, i.e., adding hops during the aging period, or after the wort has cooled and the beer has fermented.

Serving IPA

Glass: The American IPA should always be poured into a standard shaker or pint glass. This allows the beer to breathe, and you, the drinker, to observe its color and clarity, and take in the hoppy aroma. Many breweries offer screen-printed glasses emblazoned with their IPA’s label on a proper pint glass. (It might make a nice addition to your collection at home.) If your bar happens to be sophisticated enough to carry different glassware, the English IPA should be poured in the Nonic or English pint glass. The traditional pint or English pint glass both show off the beer’s rich color and frothy head. Imperial IPAs are a different breed altogether. These brews should always be served in a brandy snifter to truly capture its aroma and appreciate its overall appearance. Due to the increased potency of the Imperial IPAs, the distinguished glass should serve as a reminder to savor this special beverage instead of powering through it.

Pouring an IPA Bottle

Pouring an IPA from a tap or a bottle is pretty standard and straightforward. As with every beer, it’s most important that you start with a clean glass that’s free of debris and detergent residue. Open your bottle, bring the glass to a 45-degree angle, and aim for the middle of the glass. Begin the pour. Don’t shy away from getting aggressive with the pour, bring it on! IPAs have a fair amount of carbonation and produce a nice thick head when poured correctly. When the glass is about halfway filled, straighten it up and continue to pour into the middle of the glass. An ideal amount of head with an IPA is about half an inch. Follow the same procedure if you’re pouring from a tap.

Step 1

Step 2

Step 3

Characteristics

Appearance

An American IPA will range in color from a medium gold to a reddish copper. The color tone depends on the malt used. Almost all IPAs should be clear, with the exception of unfiltered, dry-hopped renditions. These can be a bit hazy. Many IPAs are dry hopped, but most are filtered. The head stand should persist. This means it should take at least a few minutes for the head to drop three centimeters.

Smell

The first thing that should excite your nostrils is the smell of hops. A good IPA should have an intense hop aroma. The scent should be a little bit citrusy, floral, piney, and even a bit fruity sometimes. Some might describe it as “perfume-like.” Dry-hopped IPAs will sometimes have a grassy smell. Once you get beyond the hop smell, pay attention to the presence of some sweetness from the malt.

Taste

If you’re a beer rookie, you’ll want to work your way up to an IPA. IPAs are the hoppiest beers on the market. If you’re still not sure what hoppy means, then think bitter. Hops add bitterness to beer, so lots of hops means lots of bitter. If you don’t like bitter, you won’t like IPA. If you’ve got an affinity for bitterness, a good IPA should taste much like it smells, with the same flavor characteristics. It should also taste crisp and refreshing. In your mouth, it should feel medium bodied and a bit dry. You might notice a little lingering bitterness in the aftertaste, but that should diminish quickly.

Temperature

English and American IPAs should be stored and poured at cellar temperature, between 54º F and 57º F. Imperial or Double IPAs are better served warmer, in the 57º F to 61º F temperature range. The increased temperature allows you to absorb more of the beer’s taste and aroma. If you drink a frozen beer, you are essentially freezing your taste buds and your senses. If you’re paying the extra money for one of these precious creations, take the time to enjoy it. Imperial IPAs, similar to high-quality red wines, are known to get better with age, so it doesn’t hurt to keep Imperials at cellar temperature and serve them a bit warmer. Just because IPAs were spawned from the need for a beer that could weather the elements, don’t disregard the common laws of proper beer storage (see issue No. 1). We advise doing a bit of research if you’re ever unsure about the proper serving temperature of any particular beer. Most craft breweries post specific recommended serving temperatures for their beers on their websites.

Food Pairing

IPAs are a great aperitif to enjoy prior to a large meal, no matter what the main course. IPAs pair very well with spicy dishes. The hops help cleanse the palate between bites and coat the tongue to fight the pain of spicy foods. Indian food is a natural pairing, as well as Cajun, Thai, or Mexican. Specifically, IPAs go great with pesto dishes, pork chops, grilled salmon, and soy-based dishes. If you’d like to have some cheese with your IPA, try Epoisses; it’s a pungent French cheese with a bold flavor that will stand up well to the alcohol and bitterness. If you’re down on the French, go with a Stilton, which is a British blue cheese. It’s lighter than a Gorgonzola and richer than Danish Blue. It’s a hearty cheese that goes great with any IPA.

IBU ABV

English IPAs > 40-60 5-7.5%

American IPAs > 40-60+ 5.5-7.5%

Imperial/Double IPAs > 60-100+ 7.5 – 13+%