Beer Anatomy: Stout

Words: Brad Ruppert

The awarding winning Anatomy series of articles from Beer Magazine Issue #4 May/June 2008

The stout beer or porter stout is beer that most folks recognize by its dark midnight coloring, smooth chocolaty taste, and thick motor-oil like consistency. It’s a popular beer among the Irish and most notably associated with several large breweries like Guinness, Murphy’s, and Beamish. More often than not, you’ll find that a lot of beer drinkers tend to think that the darker the beer the higher the alcohol content. Well, sadly enough, this is not the case. Using Guinness as an example, their Irish Dry Stout that comes in the tall can is only 4.2% alcohol by volume, while Budweiser lager is 5%. “That’s blasphemy!” you say. “Well I know Guinness has to have way more carbs than Bud.” Wrong again. According to RealBeer.com, Bud actually has slightly more carbohydrates than Guinness, at 10.6g to 10g per serving respectively. So why do stouts seem heavier? The chocolaty richness or coffee flavors tend to engulf our taste buds and make us think we’re consuming something a lot heavier. Another aspect is that many popular stouts are nitrogenated instead of carbonated, and this adds to the overall complexity and perceived intensity of the beer.

History

The first recorded use of the word “stout” in describing a beer occurred in the late 1600’s. A stout typically implied a strong or heavy beer and the term became common when describing high alcohol content porters. The term “porter” originated from London around the same era and referred to the beer commonly drank by the river porters that would lug around your cargo. The porter beer is a dark ale that is typically richer than other ales, having hints of chocolate, coffee, or syrup. So if we put these together, porter stouts are a darker/heavier version of a chocolaty coffee-like beer. With the growing varieties of stouts (American, Oatmeal, Oyster, Irish, Imperial) the term porter was dropped allowing the stout to stand in a category of its own.

Another interesting tidbit about stouts is their history of being used for medicinal purposes. Based on the high iron content found in stouts, it was common for people to be given a stout after donating blood. In fact, up until the early 1900’s, doctors were known for prescribing stouts to nursing mothers. Interestingly enough, the average age of breast-feeding a child in Ireland dropped dramatically from 25 years to 18 months sometime after Guinness pulled their “Guinness for Strength” campaign off the market. Hmmm… (“ ’tis a fib” , you say…. Arrrgghh, you got me… ‘ twas 24 years, actually).

The Ingredients:

Stouts, just like other beers, are made up of the classic four ingredients, malted barley, water, hops, and yeast. The distinguishing characteristic of the stout, its dark opaque color, is provided by the roasted malts used, as opposed to the traditional pale malt used when making a pale ale. Stouts also tend to be sweeter than other beers, meaning you don’t find too many being noted as hoppy.

Water: Water, the main ingredient in beer, plays a big role in the outcome of the beer’s overall taste. If you recall reading about the effects of hard water versus soft water used in beer from the last issue, we mentioned that “hard water accentuates up-front hop-bitterness while soft water actually suppresses it”. If we examine the water’s characteristics in parts per million (ppm) of both London, England (home of the Porter) and Dublin, Ireland (home of the Stout) we note that they are of similar hardness, which fall in the low to medium range compared to other beer cities around the world. These characteristics are what set the standard for how beers of this style are supposed to taste.

Yeast: What differentiates a stout from a traditional pilsner or lager, other than the most obvious color differences, is the top fermenting yeast. The stout, which is actually a dark ale, uses a yeast that works at warmer temperatures and forms a layer on the surface that eats away at the sugars and gives off carbon dioxide (CO2). Unlike the bottom fermenting Bavarian yeast that matures at -2° to 4° Celsius, the top fermenting yeast prefers 15° to 25° C and matures at 13°C. This was a limiting factor prior to refrigeration, because England and Ireland didn’t have the snowy Alps to store their beers for the long winters like the Germans did for their lagers. Most brewers use a typical ale yeast when making a stout similar to Wyeast #1084 Irish Ale Yeast.

Barley: The defining characteristic of a stout is its dark coffee-like appearance which is attributed to the roasted barley that’s used during the boiling process (making of wort). This roasted barley, which is created by cooking the grains in an oven or kiln, not only affects the appearance but also enriches the flavor of the beer. Roasted barley is often combined with chocolate malt when making stouts, which gives the beer a roasted, chocolaty, nutty flavoring. The barley also contributes to the rich white head production and stabilization of the beer.

Hops: There are a multitude of cultivars, or varieties, of hops available on the market today, each with its own properties that enhance the flavors, bitterness, and even the aroma of beer. Stouts tend to lean heavier on the sweeter or smoky properties provided by the barley and are not overwhelmingly hoppy. Typical hops used when making a stout include Bullion (used for bittering, blackcurrant aroma), Challenger (mild to moderate, spicy), Chinook (mild to medium-heavy, pine-like), or Columbus (pleasant, heavy aroma).

The Process

Back in the day, stouts were aged “stock ales” made from secondary fermentation with “Brett” or Brettanomyces, which is a non-spore forming genus of yeast. This was usually done by blending a portion of aged stout (greater than 20° Plato) into a young stout (13° Plato), which is a process known as “vatting”. The outcome of this process provided a better result than just brewing a single unblended stout of 16° P. If we look at Guinness stout, it is similar to other beers in that it relies on the basic four ingredients: water, barley, hops, and yeast, but a portion of the barley is roasted to give the beer its appearance and traditional flavor. Guinness Draught also contains a fair amount of nitrogen along with carbon dioxide which gives the beer more of a silky smooth taste, instead of a harsh effervescent sting. The high pressure of the nitrogen, when forced through the small holes in the plate of a Guinness tap, create the “sifting sand” appearance of the beer as it settles down the glass, turning from beige to black. It’s actually quite pleasing to watch (as if you needed another reason to order more beer).

Irish-Style Dry

The Irish-Style Dry Stout is probably the most recognized among the stouts due to its vast marketing and long lived history. These stouts, popularized by Guinness, Murphy’s, and Beamish, have an initial malt or subtle caramel taste with a robust dry-roasted bitterness finish. Their coffee-like or chocolaty aromas and flavors come from the roasted and chocolate barleys used in the brewing process. In fact these flavors overwhelm the taste buds and our senses of smell such that you rarely perceive any hop characteristics in these beers. Many have been nitrogen conditioned, thereby making a very smooth and creamy dark beer with a nice thick cloud-like white head.

Russian Imperial

The Russian Imperial Stout is a very complex and high gravity stout originally brewed in England with the intent of exporting to Russia and the Baltic States. This was made specific to fight the bitter cold of the harsh winters in places like Russia as well as to maintain its character throughout the long transport. American craft brewers have taken a liking to this style and revived its popularity once again. This beer is very robust, dark in color, and has a strong sense of hops in both taste and aroma. The most notable of these beers is the Old Rasputin Imperial Stout brewed by North Coast Brewing in Fort Bragg, California. This beer sets the standard for what Russian Imperial Stouts should taste like and compared to other stouts, it is like the vicious grandfather of beers. North Coast took it a step further by brewing their 10th year anniversary of Old Rasputin and aging it in bourbon barrels to make an incredible beer unmatched by any other stout.

American Imperial

The American Stout tends to be more hoppy than the Dry Irish Stout but not as hoppy as the Imperial. It has hints of caramel, chocolate, and roasted coffee with a dry-roasted bitter finish. With the American Stout, you’ll notice traces of a malty sweetness, a medium to full-bodied palate, and moderate to high hop bitterness. Even the hop aroma is noticeably present in these stouts, along with a resin-like hoppy taste. After Prohibition it took nearly 60 years for a stout to be brewed in America and only fitting that it was the first microbrewery that did it. New Albion of Sonoma California, in 1978, was the brewery to break the mold, followed by Boulder and Sierra Nevada. Nowadays you’d be hard pressed to find a brewery that didn’t make a stout.

Milk or Sweet

The Milk Stout or Sweet Stout is often more of an English Stout that includes chocolate and crystal malt. Certain types of these stouts do not use any black malt or roasted barley in their brewing process. They are called Milk Stouts because they use lactose as a sugar which is a derivative of milk. This component is not fermentable so it stands to add sweetness to the beer along with thickness and calories. And as a Milk Stout, it was only fitting that it be prescribed to nursing mothers to raise strong and healthy babies.

Oatmeal

The Oatmeal Stout, as the name would imply, is actually brewed with oatmeal, which adds to the beer’s body and sweetness. Sometimes considered a seasonal beer, the Oatmeal Stout is very dark in appearance, thick, creamy, full-bodied with a medium dry mouth feel. The amount of oatmeal added to the beer can change its taste and texture from a silky richness to an intense oily palate. The oats themselves tend to produce a nutty or earthy taste and when combined with roasted barley, the beer takes on a chocolaty or creamy coffee flavor.

Other

Other less common stouts include the Oyster Stout, Chocolate Stout, and Coffee Stout. The Oyster Stout was originally coined back in the early 1800’s when oysters were often served with a stout in many pubs and taverns. It was more of a pairing than an actual ingredient. But circa 1920, it was found that a brewery in New Zealand actually added oyster concentrate to its beer ingredients, which supposedly improved the head on the beer without adding a fishy taste. The Chocolate Stout and Coffee Stout are slight variations of the American Stout, having additional chocolate malt or actual coffee beans to enhance the flavor and aroma. What better way to start off the morning than to crack open a nice Coffee Stout before work. That’ll give ya’ a little pep in your step.

Foreign extra

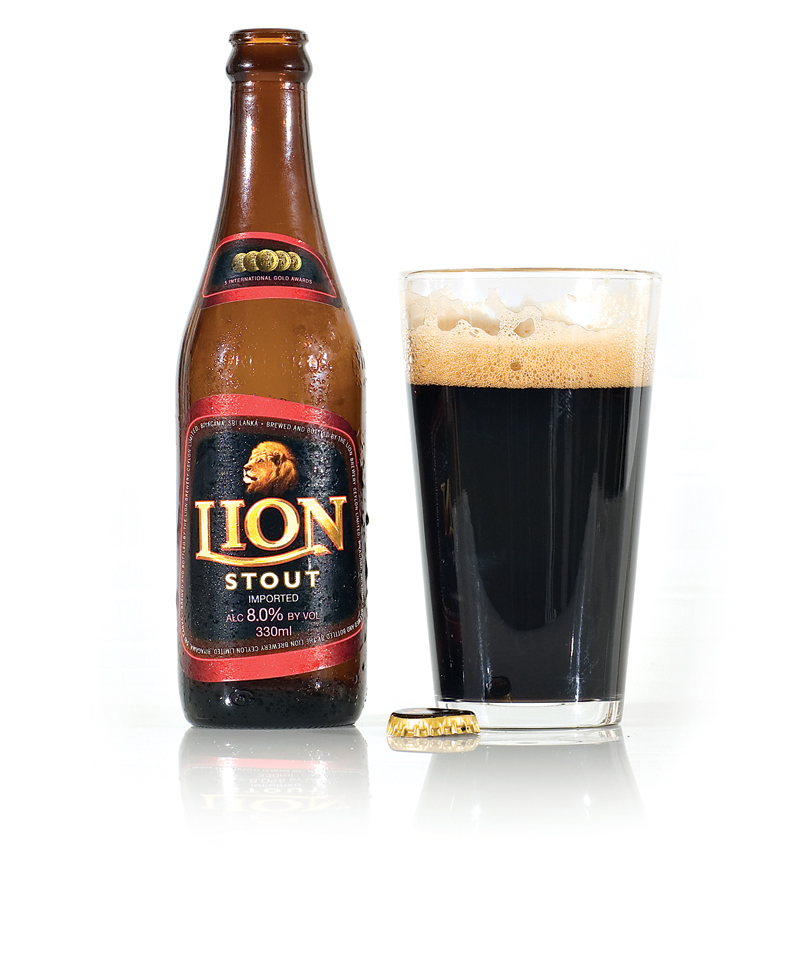

The Foreign Extra Stout was initially a select class of high-gravity stouts brewed for tropical markets. Usually more dry than sweet, they have high fruity esters, moderate bitterness, and traces of molasses or licorice. This beer has little to no hop aroma but the stronger versions have traces of alcohol scents. The hops that are added are mostly for bitterness and not for aroma. Like other stouts, it maintains chocolaty, coffee, and roasted grain flavors.

Characteristics

• Appearance

All stouts have a dark opaque appearance ranging from a rusty brown to a midnight black. The nitrogen based Irish Dry stouts usually have a white marshmallow-like head with a black base, while the American, Imperial, Oatmeal, and other stouts have a brownish-red thin bubbly head and dark base. The appearance of the nitrogen stouts, right after being poured, is one to marvel at due to the minute nitrogen bubbles that settle down the sides of the glass and give the appearance of a color changing beer from a sandy brown to a dark black. Some of the Imperial Stouts or heavier American Stouts, like Mad River’s Steelhead Extra Stout, resemble motor oil as they’re poured from bottle to glass. But make no mistake, these beers are worth their weight in gold and should be cherished as such.

• Smell

Many stouts have chocolaty or coffee aromas combined with roasted barley scents. The nitrogen stouts tend to have less aroma because they lack the carbon dioxide effervescence that other stouts have to light a fire under your senses. Imperial Stouts or American Stouts have a hoppy aroma and sometimes slight hints of varying florals or citrus smells. In Red Hook’s Double Black Stout there’s no mistaking the Starbuck’s coffee smells that come from the beans used in the brewing process. Absolutely incredible!

• Taste

Stouts are one of the richest and most flavorful beers available for consumption and also seem to have the widest array of tastes. You can get a stout that tastes chocolaty smooth, roasted coffee-like, sweet like molasses, licorice tasting, sugary oatmeal-like, hoppily bitter, or even robustly smoky. The nitrogen stouts maintain a smooth creamy sweetness flavor without the bitter acidic punch of carbonation or alcohol. Other stouts pack more of a wallop and have a heavy robust character and that keep your taste buds guessing.

Pouring

Depending on the type of stout you have, the pouring methods tend to differ. If it’s an American, Oatmeal, or Russian Imperial Stout, chances are it’s not made with nitrogen and therefore you’ll want to tilt your glass to a 45° angle to reduce excessive head (excessive head, is that possible? Well, sorry to say in beer terms, it’s not a desirable trait). After you’ve poured ¾ of the beer, straighten the glass out to finish the pour, thereby providing an ample amount of head upon that stout. Now if we’re talking about the nitrogenated stouts like Guinness, Murphy’s, or Beamish, then it’s a different story altogether. Here it’s perfectly alright to pour the beer straight up as long as you give the beer time to settle. This is usually done in two pours. First pour about ¾ of the beer into the glass and then allow it to settle. Then pour the remainder making sure to fill your beer right to the brim of the glass. This provides the perfect head and if poured from a tap, it allows the skilled bartender to engrave a clover on the surface for good luck.

Food Pairing

Chocolate or Sweet Stouts are as close to a desert beer as you can get. So, as you can imagine, they pair well with fruits like strawberries, bananas, or even shortbread or vanilla ice cream. Oatmeal or Coffee Stouts pair well with breakfast foods like eggs, bacon, hash browns, and sausage. Irish Dry Stouts are an excellent complement to hearty soups and stews or even a shepherd’s meat pie with brown gravy. Stouts can also be used when baking cakes or making pancakes; just replace the water with beer and you’re good to go. For those seafood lovers you’ll be happy to know that stouts pair extremely well with oysters as well as crab and lobster. So grab ye self a nice pint of da black gold, ya scurvy dog! Arrrrggghhh….

Common stouts

Imperial Stouts:

Avery the Czar, Bell’s Expedition Stout, Brooklyn Black Chocolate Stout, Courage Imperial Stout, Dogfish Head World Wide Stout, Founders Imperial Stout, Great Divide Yeti Imperial Stout, Great Lakes Blackout Stout, Newport Beach John Wayne Imperial Stout, North Coast Old Rasputin Imperial Stout, Rogue Imperial Stout, Samuel Smith Imperial Stout, Stone Imperial Stout, Thirsty Dog Siberian Night, Victory Storm King,

American Stouts:

Avery Out of Bounds Stout, Bell’s Kalamazoo Stout, Deschutes Obsidian Stout, Mad River Steelhead Extra Stout, Mendocino Black Hawk Stout, North Coast Old No. 38, Sierra Nevada Stout, Three Floyds Black Sun Stout, Rogue Shakespeare Stout

Foreign Extra Stouts:

ABC Stout, Black Bear XX Stout, Pike Street XXXXX Stout, Pelican Tsunami Stout, Lion Stout, Dragon Stout, Royal Extra “The Lion Stout”, Jamaica Stout, Guinness Extra Stout, Coopers Best Extra Stout, Freeminer Deep Shaft Stout, Sheaf Stout, Bell’s Double Cream Stout, Oggi’s Black Magic Stout

Oatmeal Stouts:

St. Ambroise Oatmeal Stout, Samuel Smith’s Oatmeal Stout, New Holland The Poet, Breckenridge Oatmeal Stout, Arcadia Starboard Stout, Alaska Stout, Goose Island Oatmeal Stout, Youngs Oatmeal Stout, McAusian Oatmeal Stout, Saranac Oatmeal Stout, Wolaver’s Oatmeal Stout, Harpoon Oatmeal Stout, Barney Flats Oatmeal Stout

Milk Stouts:

Moo Cow Thunder, Mackeson Triple XXX Stout, Snowplow Milk Stout, Youngs Double Chocolate Stout, Rogue Chocolate Stout, Bells Kalamazoo Stout, St. Peters Cream Stout, Alaskan Stout, Sam Adams Cream Stout, Mothers Milk Stout, Duck-Rabbit Milk Stout, Three Floyds Moloko Plus, Laughing Dog Sweet Stout

Irish Dry Stouts:

Guinness, Murhpys, Carlow Oharas Celtic Stout, Willoughby Limerick Irish Export Stout, Gritty McDuffs Balck Fly Stout, BridgePort Black Strap Stout, Bare Knuckle Stout, Three Floyds Black Sun Stout, Blue Fin Stout, Black Cat Stout, John Harvard’s Irish Dry Stout, Great Lakes Wolfhound Stout

IBU ABV

Russian Imperial Stout > 50-80 7-12%

Irish-Style Dry Stout > 30-40 3.8-5%

American-Style Stout > 35-60 5.7-8.8%

Oatmeal Stout > 20-50 3.3-5.5%

Milk Stout > 20-40 3.3-5.8%

Foreign Extra Stout > 30-70 5.5-8%